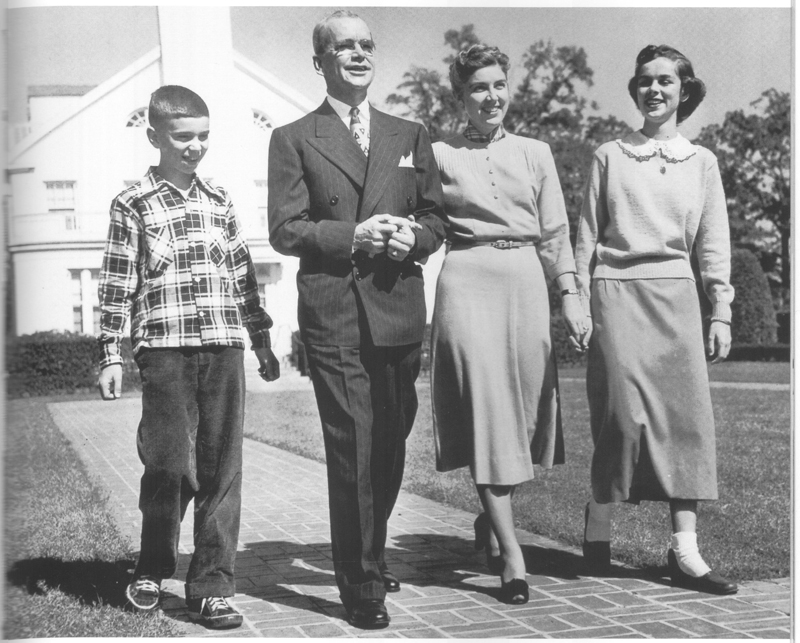

When Ralph Draughon Jr. was in high school, he was living a spoiled life at the president’s home with his father as the president of Alabama Polytechnic Institute, API. Those days seemed like Camelot to Ralph, but not to his father. President Draughon led the college through a turbulent period of change and growth, as he butted heads with the governor over desegregation.

Although Ralph and his father also butted heads, he developed a love of history like his father. After a sterling career at two museums, he returned to Auburn to find the “loveliest village” had changed, leading him to co-author “Lost Auburn.”

Although Ralph and his father also butted heads, he developed a love of history like his father. After a sterling career at two museums, he returned to Auburn to find the “loveliest village” had changed, leading him to co-author “Lost Auburn.”

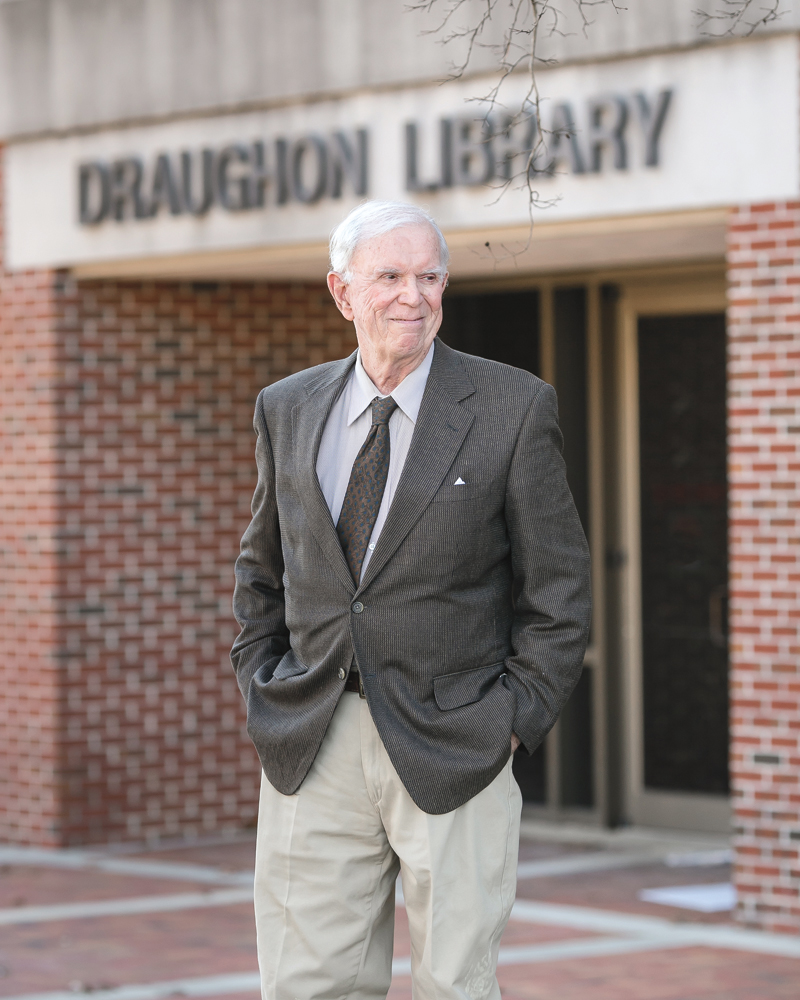

Sitting in the house in Auburn that had been his parents after his father retired as president, Ralph vividly recalls those days that led him to love his hometown. His beloved mother lived to be 94. “She had always wanted me to have this house,” he says, pointing out that the well-decorated room was as she had left it, except for his stacks of books on the desk and a table.

His father served as president from 1947 until 1965 at API, which became Auburn University under his leadership. Soon after Ralph Sr. landed in the president’s office, the Supreme Court ruled that segregation had to end. While his father was stuck between the law and Gov. George Wallace, Auburn did not have riots like some colleges in the South.

His father served as president from 1947 until 1965 at API, which became Auburn University under his leadership. Soon after Ralph Sr. landed in the president’s office, the Supreme Court ruled that segregation had to end. While his father was stuck between the law and Gov. George Wallace, Auburn did not have riots like some colleges in the South.

Ralph’s parents entertained often at the president’s mansion. He remembers one time when Gov. “Big Jim” Folsom visited, he wanted to take a nap after lunch. He was put in a guest room upstairs. “Big Jim was lying in bed with his shoes off and summoned my teen-age sister,” says Ralph. “He really scared her, but he sent her off to run an errand.”

Growing up, two of the most important people in his life were African American: Jim Smith, the college butler, who was a friend and guide to him, and Ruth Dallas, the cook. Smith kept tabs on everything going on in town, including where Ralph and his sister, Ann, had been hanging out, but never told on them.

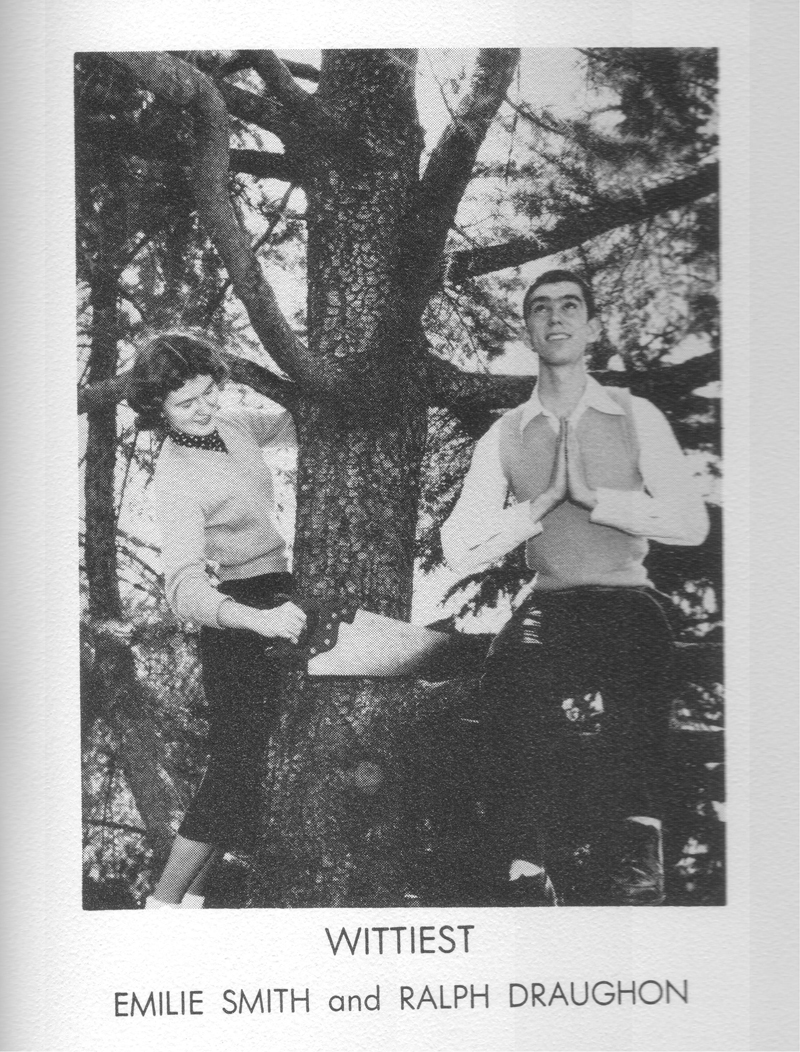

Ralph was a student at Auburn in 1957 when the football team won the national championship. He recalls there were parties and celebrations campus wide and around town. He graduated the following year and served in the Navy as a commissioned officer, stationed in Athens, Ga. and Philadelphia, Pa. While in Philadelphia, he took a course with Pulitzer Prize winner Roy Nichols at the University of Pennsylvania.

Once his tour of duty ended, he attended the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill where he received a master’s and doctoral. While working on his PhD in American history, his father asked him to speak at an annual meeting of the Alabama Historical Association, an organization he founded. Ralph remembers that generally the speaker was established and well-known, not a graduate student. “Maybe it was a peace offering,” he says, “from the years of butting heads.” He spoke on the Alabama secessionist William Lowndes Yancey. While working on his doctoral dissertation, he discovered information on the conflict between Yancey and his step-father. His speech was a success and was published and later republished. His father had planned to have a part in his graduation ceremony at Chapel Hill, but died before he graduated.

Once his tour of duty ended, he attended the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill where he received a master’s and doctoral. While working on his PhD in American history, his father asked him to speak at an annual meeting of the Alabama Historical Association, an organization he founded. Ralph remembers that generally the speaker was established and well-known, not a graduate student. “Maybe it was a peace offering,” he says, “from the years of butting heads.” He spoke on the Alabama secessionist William Lowndes Yancey. While working on his doctoral dissertation, he discovered information on the conflict between Yancey and his step-father. His speech was a success and was published and later republished. His father had planned to have a part in his graduation ceremony at Chapel Hill, but died before he graduated.

Draughon had enjoyed Athens so much when he was in the Navy that he accepted a teaching position in the history department at the University of Georgia. After being there for 11 years, he received an interesting job offer at Stratford Hall Plantation, an 18th century house to four generations of the Lees of Virginia. It was Robert E. Lee’s birthplace and also associated with two signers of the Declaration of Independence.

The house museum was owned by a group of wealthy, socialite women, including Jackie Kennedy’s mother, Janet Bouvier Anchincloss, who had restored it as a historic site and memorial to Lee. Draughon and another historian established the Monticello-Stratford Hall Summer Seminar on Colonial Virginia for high school teachers. The seminars included tours around Virginia and Williamsburg. “It was a new idea at the time,” he says. “We won an award of merit from the American Association of State and Local History.”

While there, he was asked to build a research library. When he told Mrs. Anchincloss that he was not trained as a librarian, she told him, “Just call the head of the Library of Congress, and he will give you advice.” Draughon didn’t make the call but did establish the library. He enjoyed the work, but Stratford was at an isolated location along the Potomac River. There was not a movie theater or television. After four years, he left the job in rural Virginia in 1980 to become curator of manuscripts at the Historic New Orleans Collection in the French quarter. “It was a lot of fun,” he says, “and there was always something going on in the French quarter.”

While there, he was asked to build a research library. When he told Mrs. Anchincloss that he was not trained as a librarian, she told him, “Just call the head of the Library of Congress, and he will give you advice.” Draughon didn’t make the call but did establish the library. He enjoyed the work, but Stratford was at an isolated location along the Potomac River. There was not a movie theater or television. After four years, he left the job in rural Virginia in 1980 to become curator of manuscripts at the Historic New Orleans Collection in the French quarter. “It was a lot of fun,” he says, “and there was always something going on in the French quarter.”

He was also historian for the Christopher Goodwin Archeological Firm. Draughon lived uptown in the Garden District and was enjoying his work. “Then Hurricane Katrina came along,” he says. “It blew me back to Auburn.”

Coming back home to Auburn was disappointing, as it seemed the historic character of the town had been altered. ”There is no sense of the past and no remembrance of the people who put the community together,” says Draughon. “If someone who had been away from Auburn for 50 years came back, they would not recognize the place. I think when you alter the buildings that somehow the lifestyle has been altered too. It is not the small town community that I grew up in and loved.”

Draughon, DeLos Hughes and Ann Pearson assembled the book “Lost Auburn” that is a record of buildings that are no longer standing in Auburn. It has been a best seller and is currently in a second printing. It is available at Amazon. The authors are now working on a second book with pictures and information on historic houses that are still in Auburn. Draughon is a member of the Alabama Historical Commission,

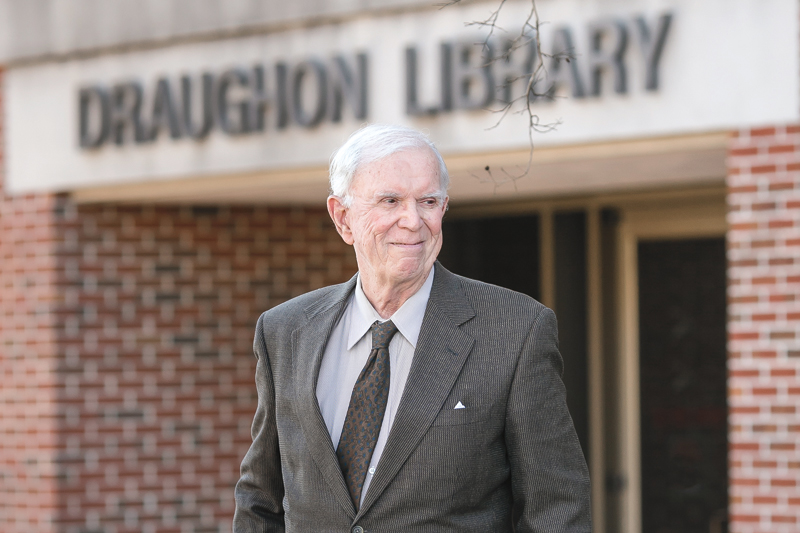

“I feel a lot of nostalgia for the place I grew up,” he says. “I have affection for black and white people who influenced me growing up. To me, my parents were so important. I feel my parents made worthwhile contributions to Auburn, and I like for them to be affectionately remembered.” The college library is named after his father, and Pebble Hill houses the Caroline Marshall Draughon Center for the Arts and Humanities. During President Draughon’s tenure, the college became a contemporary university, as he oversaw and developed much growth.

“I would like to make some small contribution,” Draughon says. “Maybe it is emphasizing the importance of preserving the history of Auburn and the structures that remind us of what Auburn used to be. “Natural and man-made disasters pale in comparison to what we ourselves have done to the loveliest village. Our bulldozers have done more damage to the town’s character than the combined effects of storms, tornadoes, fires, gas leaks, explosions and the depredations of Yankee soldiers.

“We have met the enemy,” adds Draughon, “and it is us!”